In the digital world, nudge theory has turned out to be a game-changing tool for communicators seeking to influence their audience. Better yet, it’s expected to grow even more popular with the explosion of big data and analytics. In this edition of A Communicator’s Guide To… we explore how governments are using nudge theory to supercharge their communications, and how you can get in on the action.

What is nudge theory?

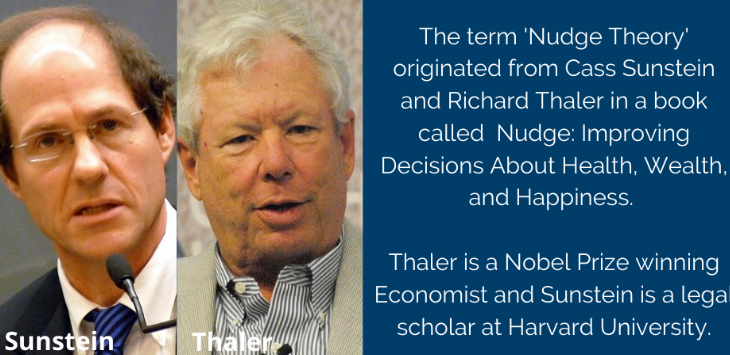

Nudge theory is a popular concept in behavioural economics and policy making. It outlines indirect strategies that ‘nudge’ individuals or groups towards a desired outcome.

Image Sources: Left: Matthew Hutchins, Harvard Law Record. Right: Chatham House.

Nudge theory bypasses harsher methods of persuasion such as strict bans or uses of force by carefully influencing the way that citizens make decisions. This might mean presenting citizens with new or relevant information to inform the choices they make, altering physical environments like shop or city layout, making policies ‘opt-out’ rather than ‘opt-in,’ or informing citizens about how their behaviour relates to social norms.

One example is the introduction of plain packaging laws for cigarettes in 2011. The Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 stipulates exactly how cigarette packages must be designed, with the goal of reducing their appeal. These laws ‘nudge’ Australians away from purchasing cigarettes, without actually preventing them from doing so.

How is Government using nudge theory?

In 2016, the Australian Government set up the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government (BETA) within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. BETA works on a number of projects across government to trial the use of behavioural economics and nudge theory.

In a recent project, BETA collaborated with Westpac. The bank identified 24,000 consumers with a history of making low repayments on their credit card debt, and BETA tested a range of communication methods to encourage customers to make higher repayments.

They found that email notifications had no impact, but that sending customers short text messages increased average monthly repayments by 28%. The right nudge to the right customer at the right time led to significantly improved outcomes.

In more recent times, governments have been turning to nudge to establish coronavirus guidelines. For example, insights into citizen perceptions of depth and distance have been employed to make messaging around social distancing as clear as possible, while other endeavours are in place to reduce the amount of PPE waste produced.

Why is nudge theory important for communicators?

Nudge theory is an incredibly powerful and relevant tool for communicators, but it can be tricky to implement. How can we communicate the benefit of one choice over another, whilst respecting a citizen’s right to make their own decisions?

The whole basis of nudge is understanding the behaviour of your audience and the incentives they care about. These insights can then inform your communication strategies. Fortunately, knowing your audience is easier than ever, with incredible insights available via social media and open source data – in fact, the International Data Corporation expects 175 trillion gigabytes of digital data to be created worldwide by 2025.

By harnessing the power behind this data, communicators can use nudge theory to engage with and motivate their audience.

Nudge theory is also a great lens through which to review communication channels and platforms. With more ways of reaching our audience than ever before, the principles of nudge theory can help communicators determine which channel will have the most impact.

While units such as BETA exist, government communicators don’t need to work directly with these organisations to incorporate nudge theory in their day-to-day work. In fact, there are a number of online resources on the BETA website that communicators can use to bolster their strategies with an injection of psychological and economic insights.

The risks of Nudge Theory

Although nudge is one of the leading theories in behavioural economics, it is not without its critics.

One concern about nudge theory is how to draw the line between nudge and manipulation. How does one balance an individual’s freedom to choose with the Government’s responsibility to protect the greater good? Can nudge go too far and become Government overreach?

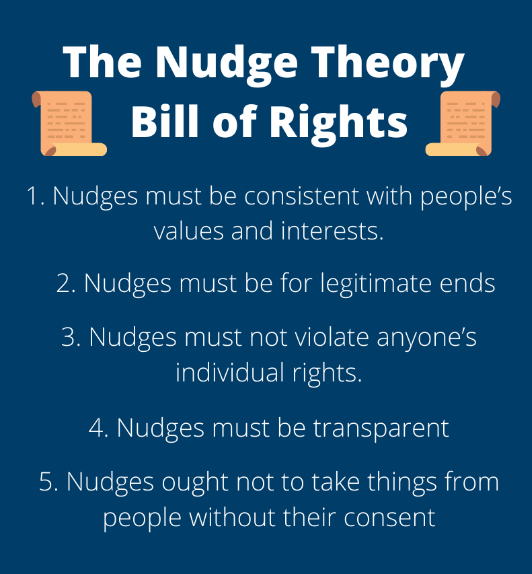

Cass Sunstein has written a ‘Bill of Rights’ for nudge theory that can help practioners to stay within the guard rails of ethical and effective nudging. It’s worth a read before you start your next campaign.